Contents

- Contents

- Introduction

- Letters

- Pronunciation

- Parts of speech

- §15.Sorts and categories

- §16.Decoratives

- Inflections

- Basic sentence structure

- Negatives

- Questions

- Usages of verbs

- §32.Tenses

- §33.Aspects

- §34.Transitivities

- Special verb structures

- Passives

- Comparison

- §39.Comparatives

- §40.Equatives

- §41.Superlatives

- Relative constructions

- Conjunctions

- Numerals

- §48.Numbers

- §49.Use of numerals

- §50.Nominal forms of numerals

- §51.Dates and times

- Omission and contraction

- Rhetorical expressions

- §58.Insertion

- §59.Emphasis

- §60.Admiration

- §61.Irony

- Other special expressions

- Other important words

- §65.Proforms

- §66.Interjections

- Colloquial expressions

- Detailed explanations for categories

Introduction

§1.Effective date

The grammar of version 6 of the Shaleian language has been used since 26/09/04 of the Hairia calendar (07/Nov/2015 of the Gregorian calendar). Note that sentences written before that date are based on an older grammar and cannot be interpreted using the current one.

§2.Note on notation

In this document, all sentences in Shaleian are written in a Latin transliteration. In order to avoid confusion, a roman typeface is used for the normal text, while a sans-serif typeface is used for words or sentences in Shaleian.

§3.Note on reading

The sections in this document are arranged in such an order that it is easy for advenced learners to check the grammar, not for beginners to learn the language for the first time. Beginners are recommended to read the introduction first.

Since this document is meant to explain the grammar of the Shaleian language, it does not deal with detailed usages such as collocations except for ones closely related to the structure of sentences. All explanations are based on the written language. Expressions peculiar to the spoken language will be taken up separately in Section 67 and Section 68.

§4.Changes from version 5.4

Changes from version 5.4 are listed below:

- long vowels and diphthongs are shortened (Section 11)

- the consonant inserted between adjacent vowels is changed (Section 12)

- the position of stress is changed (Section 14)

- the pronunciations of stressed vowels are changed (Section 14)

- the negative becomes a prefix (Section 24)

- short forms for cardinal and ordinal numerals (Section 49)

- expression of time (Section 51)

- abbreviations for dates and times (Section 56)

Letters

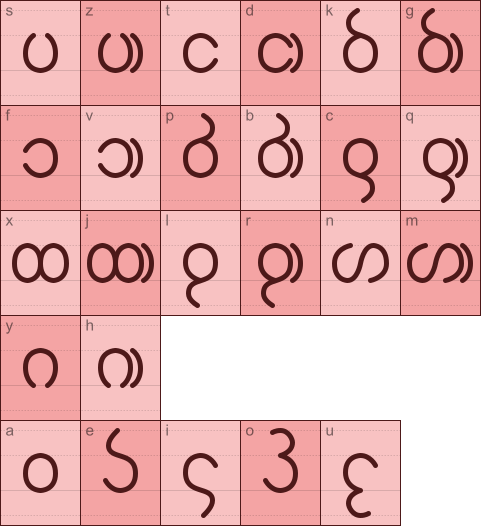

§5.Alphabets

The Shaleian language is written with the 26 letters in the “Shaleian alphabet”. These are all phonograms; namely, each letter corresponds to exactly one phoneme. See Section 10 for the details of this correspondence.

Since the Shaleian alphabet is unique to the Shaleian language, it is, of course, not covered by Unicode. Therefore, it is difficult to input or display the script on computers. For this reason, the Latin alphabet, with each letter corresponding to a Shaleian letter, is often used instead. This notation is called the “Latin transliteration” (or the “romanisation”). The transliteration is also used to make sentences easier to read for beginners not familiar with the Shaleian alphabet.

The small letters are listed as follows. A figure at the center of each cell illustrates the shape of a Shaleian letter, with its Latin transliteration at the top-left corner.

Furthermore, some letters can receive diacritical marks. See Section 8 for details.

In 15/10/06 of the Hairia calendar (29/Nov/2017 of the Gregorian calendar), the letterforms of the Shaleian alphabet were revised; the forms listed on this page are the post-revision forms. From this revision on, the new forms are used as the primary forms, but the old forms may be used as well. Consult the grammar before the revision for the old alphabet.

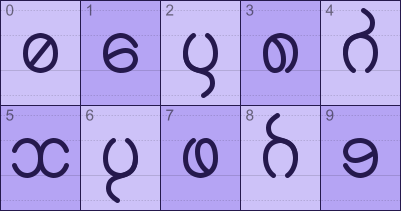

§6.Numerals

Shaleian adopts the decimal numeral system for denoting numbers. Therefore there are ten digits, which are listed below. The pronunciation and usage of the numerals will be explained in Section 48 and Section 49.

Numerals are written sometimes in digits such as dev il'6 or ben ic'12, and sometimes in their pronunciation such as dev il'aric or ben ic'atisetqec.

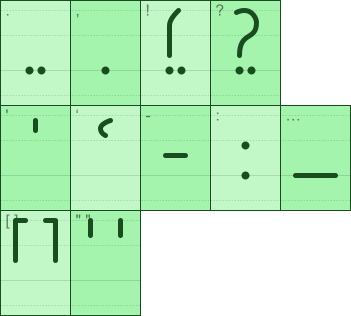

§7.Punctuation marks

Shaleian mainly uses the punctuation marks listed below:

Each mark is used as follows:

| trans | name | role |

|---|---|---|

| . | dek | indicates the end of a sentence |

| , | tadek | indicates a pause in a sentence |

| ! | vadek | indicates the end of a sentence with emphasis |

| ? | padek | indicates the end of a interrogative sentence |

| ' | nôk | indicates a contraction |

| ʻ | dikak | marks the following word as a proper noun |

| - | fêk | makes a compound word |

| : | kaltak | partitions data |

| … | fôhak | indicates a silence or a lingering |

| « » | rakut | specifies that the expression inside is a dialogue |

| “ ” | vakut | specifies the expression inside is a quotation or emphasised |

Points contained in deks, tadeks, vadeks and padeks are sometimes written by hand with a sweeping stroke like commas.

Tadeks indicate a pause in a sentence, but their use is restricted to certain positions and therefore are not completely free. They are, for example, put after a nonrestrictive use of a relative clause, mentioned in Section 43, or an adverbial use of a conjunction, mentioned in Section 44. Nôks are used in place of the omitted letters when a contraction occurs. Contractions will be explained in more detail in Section 55. Dikaks are put immediately before a word and indicate that it is a proper noun such as a person's name. The uses of fêks and kaltaks will be dealt with in Section 57 and Section 56, respectively.

Both rakuts and vakuts correspond to quotation marks. The former are used only for conversations, while the latter are for quotations and emphases.

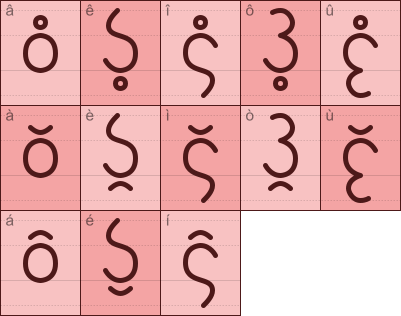

§8.Diacritical marks

The five letters a, e, i, o and u are sometimes used with one of the three diacritical marks as displayed in the following table. Letters with and without diacritics are treated as distinct letters.

Diacritics are not omitted in a normal text, but sometimes omitted when some decoration is applied to letters with them, such as in a poster.

§9.Alternative transliteration

As mentioned in Section 8, the transliteration of Shaleian alphabets uses Latin alphabets with diacritical marks, such as â or á. In the case where technical difficulties prevent the use of diacritics, the alternative notation, listed below, may be used.

| formal | alternative |

|---|---|

| â (U+00E2) | aa |

| ê (U+00EA) | ee |

| î (U+00EE) | ii |

| ô (U+00F4) | oo |

| û (U+00FB) | uu |

| á (U+00E1) | ai |

| é (U+00E9) | ei |

| í (U+00ED) | ie |

| à (U+00E0) | au |

| è (U+00F8) | eu |

| ì (U+00EC) | iu |

| ò (U+00F2) | oa |

| ù (U+00F9) | ua |

| ʻ (U+02BB) | ' |

The alternative notation should be avoided as much as possible. It is highly recommended to use the formal transliteration unless technical issues prevent its use.

Pronunciation

§10.Letters and their pronunciation

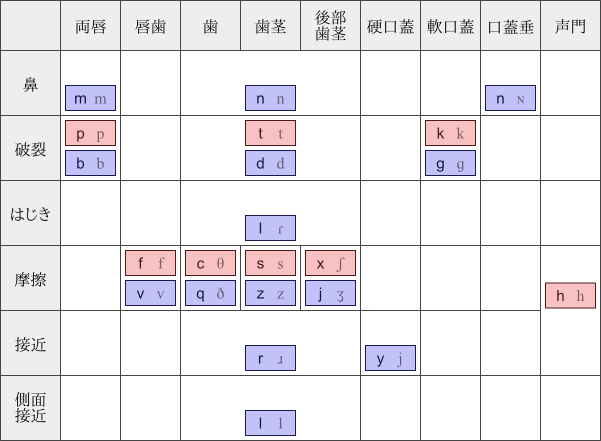

Shaleian uses the following consonants. A letter at the left of a phonetic symbol indicates the (transliteration of) the corresponding Shaleian letter.

The letter l has complementary allophones; it is pronounced /l/ when a vowel follows it, and /ɾ/ otherwise. The phoneme /w/ appears only between a succession of certain letters (see Section 12 for details). The usage of /ɴ/ will be explained later.

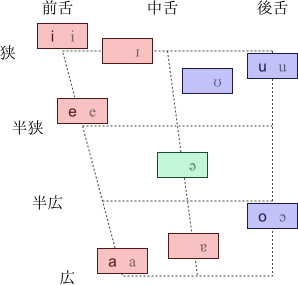

The vowels are listed below. The pronunciation of letters with diacritics will be explained in Section 11.

The four vowels /ɪ/, /ʊ/, /ɐ/ and /ə/ appear as the second vowel of a diphthong, mentioned in Section 11, and do not appear alone.

Basically, all letters are pronounced according to the correspondence of letters and phonemes displayed in the preceding tables, except when some phonological changes (described in Section 12) occur. There are, however, a small number of exceptions. For example, kin is pronounced /kiɴ/; the phoneme /ɴ/ appears only in kin and its contraction 'n. The letter h also has a phonological exception. When it is placed at the end of a syllable, it may be pronounced /h/, but in most cases, it is not pronounced at all.

§11.Long vowels and diphthongs

The letters â, ê, î, ô and û originally represented long vowels and were pronounced slightly longer than those without diacritics. Nowadays, however, they are usually pronounced like the corresponding letters without diacritics without lengthening them.

The other letters, á, é, í, à, è, ì, ò and ù, were originally pronounced as in the table below. Each of these diphthongs forms one syllable.

| letter | pronunciation |

|---|---|

| á | /aɪ/ |

| é | /eɪ/ |

| í | /iə/ |

| à | /aʊ/ |

| è | /eʊ/ |

| ì | /iʊ/ |

| ò | /ɔɐ/ |

| ù | /uɐ/ |

As is the case with the long vowels, these diphthongs are also pronounced in the same way as the corresponding short vowels in many cases. Even so, however, the three connectives with diacritics (ò, á, é and à) and their alternative forms (lá, lé and dà) are pronounced according to the table above in order to distinguish them from other words.

§12.Phonological changes of consecutive vowels

When one of the following eight patterns of consecutive vowels appears within a single word, it is pronounced with a certain semivowel inserted between its first and second vowels. These patterns are seen in words borrowed from other languages.

| pattern | pronunciation |

|---|---|

| ia | /ija/ |

| ie | /ije/ |

| io | /ijɔ/ |

| iu | /iju/ |

| ua | /uwa/ |

| ue | /uwe/ |

| ui | /uwi/ |

| uo | /uwɔ/ |

If two vowels are adjacent between two words (rather than within a single word), or in other words, if a word ending with a vowel precedes a word starting with a vowel, then /l/ is inserted between those two vowels in order to avoid the hiatus. However, /l/ is not inserted if the second word is a proper noun.

§13.Syllable structure

Every syllable in Shaleian takes one of the following four forms: V, CV, VC and CVC. Two (or more) consonants cannot be adjacent within a single syllable. Every long vowel or diphthong is counted as a single vowel, and consecutive vowels form distinct syllables.

If a word contains consecutive consontants within a syllable when borrowed from a foreign language, e is inserted between the consonants as appropriate to divide the syllable.

§14.Accent

In Shaleian, accent is produced through stress, not through pitch. Accented vowels are pronounced slightly longer than other vowels.

Every word has an accent on the last vowel of its stem. Here, a “stem” means the part of a word obtained by removing all attached inflected affixes and negative prefixes from it.

Parts of speech

§15.Sorts and categories

Shaleian has seven parts of speech: verbal infinitives, nominal infinitives, adverbial infinitives, functionals, particles, connectives and interjections. These are called “sorts” in Shaleian. Every word is classified into exactly one sort, and no words belong to two or more sorts. For example, the word yerif is a verbal infinitive, and it is not simultaneously classified as a nominal infinitive or in any other sort.

On the other hand, the same word in Shaleian may play multiple different roles in sentences. Such a role in sentences is called a “category”. There are seven kinds of categories: verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections. Every word may be used in multiple categories. For example, yerif, whose sort is verbal infitive, has four categories: verb, noun, adjective and adverb.

As shown in this table, the categories a word can take are completely determined by its sort. A word cannot be used in a category not allowed by its sort.

| sort | category |

|---|---|

| verbal infinitive | verb, noun, adjective, adverb |

| nominal infinitive | noun |

| adverbial infinitive | adverb |

| functional | adverb |

| particle | preposition, conjunction |

| connective | conjunction |

| interjection | interjection |

However, the frequency at which a word is used in a given category depends on the particular word. For example, yerif, which is a verbal infinitive, is mostly used as an adjective but only rarely as a verb. On the other hand, kût, which is also a verbal infinitive, is mostly used as a verb but only rarely as an adjective.

§16.Decoratives

In Shaleian, morphemes that are placed before or after other words and change their meanings, usually called prefixes or suffixes, are called “decoratives”. Decoratives do not include inflected affixes. Since they are not independent words, they are not classified into any sort.

Inflections

§17.Inflections of verbal infinitives

Verbal infinitives change their form depending on their categories in sentences. To put it simply, they are inflected by attaching prefixes or suffixes to their stems, which are listed as headwords in dictionaries.

When a verbal infinitive is used as a verb, it is conjugated by attaching two suffixes to its stem. The first one indicates its tense, and the second one indicates its aspect and transitivity. The following table shows the tense suffixes:

| suffix | tense |

|---|---|

| a | present |

| e | past |

| i | future |

| o | indeterminate |

The following table shows the aspect-transitivity suffixes:

| suffix | aspect, transitivity |

|---|---|

| f | inceptive, intransitive |

| c | progressive, intransitive |

| k | perfect, intransitive |

| t | continuous, intransitive |

| p | terminative, intransitive |

| s | indeterminate, intransitive |

| v | inceptive, transitive |

| q | progressive, transitive |

| g | perfect, transitive |

| d | continuous, transitive |

| b | terminative, transitive |

| z | indeterminate, transitive |

For example, when the verbal infinitive sâf is used as an intransitive verb with the past tense and the terminative aspect, it is conjugated sâfep.

When a verbal infinitive appears as an adjective or an adverb, one of the following prefixes is attached before it.

| prefix | category |

|---|---|

| a | adjective |

| o | adverb |

The meanings of tenses, aspects, and transitivities of verbs are explained in Sections 32–34.

§18.Inflections of adverbial infinitives

Adverbial infinitives are used only as adverbs. They always appear with inflected prefixes e and do not appear independently without prefixes.

§19.Inflections of particles

Particles are divided into two types. One comprises those which can be used as prepositions in the form of their stems, or in other words headwords of dictionaries. The other consists of those which cannot be used alone as prepositions and always appear with inflected prefixes. Particles of the former type are called “normal particles”, and those of the latter type are called “special particles”.

When normal particles are used without prefixes, they form phrases which modify verbs, but when the inflected prefix i is attached to them, they form phrases which modify words other than verbs. For example, the particle te forms a prepositional phrase modifying a verb in the form of te, while it modifies a nonverb, such as a noun, in the form of ite. The form to which the prefix i is attached is called a “nonverb-modifying form”.

Special particles, as prepositions, cannot be used independently and always appear with the prefix i.

Both normal and special particles are used in the form of their stems when they are used as conjunctions.

We will discuss the basic use of prepositions in Section 20 and Section 21, and nonverb-modifying forms in Section 36 and Section 63.

Basic sentence structure

§20.Preposition + noun

In Shaleian, nouns are always used with prepositions put before them, and do not appear independently. Such a cluster of a preposition and a noun is called a “prepositional phrase”. Terms such as “a-phrase” or “te-phrase” are used to explicitly express the preposition used in such a phrase.

Prepositions indicate the grammatical cases of the accompanying nouns.

- câses a tel e yaf.

- I met my sister.

The sentence above has two prepositional phrases: a tel and e yaf. The preposition a included in the phrase a tel indicates that tel is used as a subject of the sentence, and the e in e yaf indicates that yaf is an object of the verb.

Nouns are always accompanied with prepositions, but not all prepositions are used with nouns only. When (and only when) prepositions qualify certain verbs, they may take adjectives as complements.

- salat a nayef aquk e abig.

- That flower is blue.

Here the adjective abig accompanies with the preposition e. Along with sal, the verb nis also allows such prepositional phrases.

There are two kinds of prepositions: one modifies verbs by forming a prepositional phrase, while the other modifies nonverbs. A preposition of the former kind is called a “verb-modifying preposition”, and the latter kind of preposition is called a “nonverb-modifying preposition”.

- qetat a nîl i tel vo fîc ica fêd.

- My brother is around here.

In this sentence, the nonverb-modifying preposition i modifies nîl in the form of i tel. In addition, ica, which is inflected to be used as a nonverb-modifying preposition, modifies fîc in the form of ica fêd.

§21.Verb + prepositional phrase

At a basic level, every sentence in Shaleian consists of a verb at the beginning with verb-modifying prepositional phrases lined up after it.

- cates a tel.

- I walked.

In the sentence above, the verb cates is put at the beginning of the sentence and followed by the prepositional phrase a tel, which modifies it and expresses its subject.

There can be more than one element modifying a verb. In this case, the elements modifying the verb are lined up one after another.

- feges a tel e dezet vo vosis afik.

- I bought a chair at this shop.

In this sentence, the verb feges is modified by three postposed elements: a tel, indicating the subject, e dezet, indicating the object, and vo vosis afik, indicating the place. Here one can freely choose the order of modifying elements. Therefore this sentence can be rewritten as feges vo vosis afik a tel e dezet. Note that the grammar does not restrict the order of prepositional phrases, but the nuance of a sentence changes depending on which phrase is placed first, as explained more fully in Section 23.

§22.Adjectives and adverbs

In general, modifiers follow their heads, in the same way that phrases modifying verbs are put after the verbs. This rule applies to nouns and adjectives as well: adjectives are placed after nouns that they modify.

- lices a tel e nayef azaf.

- I looked at a red flower.

In the example above, the adjective azef qualifies the preceding noun nayef. When more than one adjectives modify a noun, they are placed in a row, just as verb-modifying phrases are put after verbs. The order of adjectives makes almost no difference in nuance.

- kûtat a tel e dev axodol ajôm.

- I have an expensive black pen.

In this sentence, the two adjectives axodol and ajôm modify the noun dev. One can change the latter half of it into e dev ajôm axodol without changing its nuance. Note that qualifying proforms, introduced in Section 65, are placed after other adjectives qualifying the same noun.

- salat e ayerif a nayef anav afik.

- This yellow flower is beautiful.

Since the word afik in this example is a qualifying proform, it is put at the very end of the adjectives. It is ungrammatical to change the e-phrase into a nayef afik anav.

When an adverb modifies an adjective, it is put after the adjective according to the rule of placing modifiers after heads.

- séqes a tel ca ces e xoq anisxok ebam.

- I gave him a very interesting book.

In this sentence, the adjective anisxok qualifies the preceding noun xoq, and the adverb ebam qualifies anisxok similarly.

When adverbs modify a verb, they are placed between the verb and the first prepositional phrase or at the end of the sentence. They cannot be put between two prepositional phrases unless they are used as insertions, mentioned in Section 58.

- vilises omêl a tel.

- I ran slowly.

In the example above, the adverb omêl is interposed between the verb and the first prepositional phrase, and modifies the verb vilises.

§23.Order of prepositional phrases

As mentioned in Section 21, prepositional phrases can be ordered freely. There is, however, a convention for ordering prepositional phrases.

In Shaleian, a focus falls on the end of a sentence; the beginning introduces a topic and the end offers information about it. Therefore, prepositional phrases are ordered so that the topic, which has already been brought up in the context, comes at the beginning, and new information, which has not yet been mentioned, comes at the end.

- qoletes a tel e zeqil. séqes e cit ca tel a refet.

- I sold a table. It was given to me by my friend.

When the first sentence is about to be written, there is no prior information. In such a case, the subject is usually placed at the first. The sentence then gives information zeqil to the reader at the end to convey the information that “a table was sold”. Thus, since the phrase e cit appears at the first prepositional phrase of the second sentence, the reader can easily understand that this “cit” is the table mentioned in the previous sentence. Moreover, since e refet comes at the end, the reader obtains new information that the table was given by a friend of “tel”.

Here, the prepositional phrases in the second sentence are transposed:

- qoletes a tel e zeqil. séqes a refet ca tel e cit.

- I sold a table. My friend gave me that table.

When the reader begins to read the modified version of the second sentence, he/she would suddenly get the new information of “a friend” while “a desk” is in his/her head. As a result, he/she might wonder “what happened to the desk?” and get confused. When the reader finishes reading the second sentence, he/she would finally realise that this sentence is about the desk mentioned previously. Thus, the reader has trouble understanding the sentences.

As stated above, prepositional phrases are ordered so that the reader can smoothly obtain information.

Negatives

§24.Normal negatives

Negatives can be made by attaching the prefix du, which indicates negation, to the verbs of affirmative sentences. Since du is a prefix, no space is inserted between du and the negated word.

- dusâfat a tel e loc.

- I do not like you.

The negative du can negate words other than verbs, such as adjectives and adverbs. In such a case, du is placed after any inflected prefixes.

- câses a tel te tazik e fér aduhál.

- I met a girl who is not cute yersterday.

In this example, the adjective ahál is negated to mean “not cute”.

When du is attached to nouns, it gives the meaning of “something other than …”.

- salot a tel e dutific.

- I am not a child.

In this case, by negating the noun tific, not the verb, the sentence implies that “tel” is something other than a child, that is, a grown-up.

§25.Partial and total negation

The negative du negates only the single word following it. One can apply this property to construct sentences with partial or total negation.

Placing the negative before a verb in a usual manner forms total negation.

- dudéxat ovák a ces.

- He is never sleeping.

In this sentence, du negates only déxat, and dudéxat alone stands for “not sleeeping”. Since the phrase “not sleeping” is qualified by ovák, meaning “always”, the whole sentence means “always not sleeping” or “always awake”.

On the other hand, when du is attached to a word representing “all” or “nothing”, it forms partial negation.

- déxat oduvák a ces.

- He is not always sleeping.

In this case, du negates only ovák to form oduvák, which means “not always” or “with a temporal exception”. oduvák then modifies déxat, meaning “sleeping”, and thus these words together mean “sleeping with a temporal exception” or “not always sleeping”.

The following list shows words which form partial negation in this way.

| word | meaning |

|---|---|

| aduves | not all … |

| odukôt | not necessarily … |

| oduvák | not always … |

| oduvop | will never … again |

By negating the whole kin-clause in the form of dulesos e kin …, one can also make a sentence with partial negation.

- dulesot e kin déxas ovák a ces.

- He is not always sleeping.

In the sentence above, the kin-clause, meaning “he is always sleeping”, is negated; therefore, the whole sentence forms a partial negation meaning “he is not always sleeping”.

§26.Negative words

Shaleian has several words which have a negative meaning without the negative prefix. Such words are called “negative words”. As an example, dus means “zero people” or “nobody”.

- keqit a dus e sod afik.

- Nobody will live in this house.

Some words that represent zero can be replaced with the negtive prefix and a noun without changing their meanings.

- dukeqit a ris e sod afik.

- Nobody will live in this house.

The following table displays the major negative words. Each negative word is fixed to be used as a certain category, which is also listed below.

| word | meaning | category |

|---|---|---|

| dus | nobody | noun |

| dat | nothing (for objects) | noun |

| dol | nothing (for events) | noun |

| dûd | no place | noun |

| dak | no | adjective |

| dûg | never (for probability) | adverb |

| dum | never (for frequency) | adverb |

The first five words in the table are proforms, discussed in Section 65. As mentioned above, one can replace them with the negative prefix and an elective proform for these negative words.

§27.Double negation

When a negative word, explained in Section 26, and the negative prefix are used simultaneously to form a double negative, the sentence makes strong affirmation.

- dusalat a dol e asokes.

- Nothing is not important.

This sentence means “everything is important”. By using double negation, one can claim more strongly than simply saying salat a zel aves e asokes.

Questions

§28.Polar questions

Polar questions ask whether something is true or not; the reply is expected to be either “yes” or “no”. One can construct such a question by placing pa before the verb of a sentence which represents what one wants to verify. The word pa is named an “interrogative adverb”. In addition to that, the dek at the end of the sentence is exchanged for a padek. No changes in word order are made.

- pa kilat lakos a loc qi qixaléh?

- Can you speak Shaleian?

Questions are read with rising intonation.

One uses ya or du to answer polar questions. They are both interjections, discussed in Section 65. The answer ya is used when what the question asks is true, while du is used when it is false.

- pa séqes ca loc a ces e gisol? / du.

- Did you get money from him? / No.

Pay special attention to answering ya or du when the question is a negative sentence. One uses ya when the sentence obtained by removing pa from the question is correct, and du otherwise. Therefore, they are used in a different manner from English “yes” and “no”.

- pa dusâfakes a loc e dat? / ya.

- Don't you like dogs? / No.

In this example, the sentence obtained by removing pa has the meaning “you do not like dogs”, so a person who answered ya does not like them.

§29.Nonpolar questions

Questions with interrogatives can be constructed by replacing what one wants to ask with an appropriate interrogative and placing pa before the verb in the same way as making polar questions. Moreover, the dek at the end of the sentence is replaced with a padek. The sentence is read with rising intonation.

- pa salot a loc e pas?

- Who are you?

- pa sâfat a loc e fakel apéf?

- What sort of woman do you like?

The following table shows the main interrogative words. Each word is used only in certain categories, so the categories are also listed.

| word | meaning | category |

|---|---|---|

| pas | who | noun |

| pet | what, which (for objects) | noun |

| pil | what, which (for events) | noun |

| pâd | where | noun |

| pek | what kind of | adjective |

| péf | how | adjective, adverb |

One can form interrogative phrases not included in the table above by combining prepositions and interrogative pronouns. For example, combining the interrogative pil with the preposition vade, indicating a reason, yields a phrase meaning “for what reason” or “why”.

- pa qoletes a loc e sod vade pil?

- Why did you sell your house?

Examples of interrogative phrases made after this method are the following:

| phrase | meaning |

|---|---|

| te pet | when, what time |

| vade pil | why, for what reason |

| qi pil | how, by what means |

To answer a nonpolar question for which the answer is a noun, one uses a phrase in the form of a preposition + a noun.

- pa lanes a loc ca amerikas te pet? / te tazik.

- When did you go to America? / Yesterday.

In most cases where the interrogative word is pil, the answer is a nominal clause. In this case, one answers with the form of a preposition + kin + a clause.

- pa leses a loc te tazik e pil? / e kin câses a tel e ʻyutih.

- What did you do yesterday? / I met Yutia.

When an interrogative adjective is used, the answer is also an adjective. In this case, one answers with the form of a preposition + a noun + an adjective. One cannot answer with only an adjective.

- pa sâfat a loc e zas apéf? / e zas asafey.

- What kind of people do you like? / Those who are friendly.

§30.Choice questions

Choice questions, which require choosing one (or more) among several alternatives, can be constructed by creating a nonpolar question and specifying the alternatives with the preposition ive. Since the ive-phrase qualifies the interrogative, it is put immediately after the interrogative. The alternatives are connected by the conjunction o. When there are more than two alternatives, o is interposed between each of the options. Shelaian has no equivalent for the word “which”, so pas, pet or pil is used instead.

- pa sâfat a loc e pet ive zef o bag o nev?

- Which do you like, red, blue or yellow?

There is another way to construct a choice question: two or more sentences can be connected with the conjunction á, which means “or”. Note that the interrogative adverb pa is needed for the sentence after each á.

- pa salat a qut e ahap emic, á pa salat a fit e ahap emic?

- Is that cheaper, or is this cheaper?

This sentence is redundant because of repeated phrases, so one of the common phrases is usually omitted as in the following:

- pa salat a qut e ahap emic, á pa lat a fit?

- Is that cheaper, or is this?

The latter of the phrases e ahap emic shared by the two clauses is omitted and the proverb l is used instead. The use of such an omission will be discussed in detail in Section 54.

Since the last sentence is still redundant, the two clauses are often integrated into one clause as in the following:

- pa salat e ahap omic a qut á fit?

- Which is cheaper, this or that?

As another form of choice questions, there are those which require choosing an affirmative or a negative, namely, those meaning “whether or not …”. These are constructed by connecting affirmative and negative questions with the conjunction á.

- pa debat e loc, á pa dudebat e loc?

- Are you tired, or aren't you tired?

To avoid redundancy, the common phrase is omitted by the second clause to form the following sentence:

- pa debat e loc, á pa dulat?

- Are you tired, or not?

Otherwise one can move dulat in the second clause just behind the verb in the first clause, as in the following sentence. This form is preferred when the first clause is long.

- pa debat á dulat e loc?

- Are you tired or not?

§31.Indirect questions

In the case where a nonpolar or choice question forms a part of a sentence, it can be embedded after the interrogative adverb pa is removed from it.

For example, consider the following question:

- pa qetat a sod i loc vo pâd?

- Where is your house?

To embed this question in another sentence, one removes pa from it and use a kin-clause as follows. Note that since the new sentence is not a question, we put a dek at the end, not a padek.

- sokat a tel e kin qetat a sod i loc vo pâd.

- I know where your house is.

We will discuss in Section 47 the details of the conjunction kin used in this sentence.

Polar questions are embedded in a sentence in a different way. As an example, we construct an indirect question using the following sentence:

- pa kavat a loc e nîl?

- Do you have brothers?

We first rewrite this sentence by using an expression with the conjunction á meaning “whether or not …”, as explained in Section 30.

- pa kavat a loc e nîl á pa dulat?

- Do you have brothers or not?

Next, we embed the rewritten question in the same manner as other types of questions. The two interrogative adverbs pa must be removed.

- dusokat a tel e kin kavat a loc e nîl á dulat.

- I don't know whether or not you have brothers.

Usages of verbs

§32.Tenses

Shelaian has four tenses: present, past, future and indeterminate.

The present tense is used to express what is happening at the current moment.

- xôyak a tel e sokul.

- I have finished tidying up the room.

The past tense is for events which happened in the past. Events expressed in the past tense do not have any relationship to the present time.

- zedotes a tel e miv aquk.

- I tore that paper.

In this case, since the past tense is used, it expresses only that the paper was torn at a certain point in the past, and it does not mention whether the paper is still torn or restored at the present time. On the other hand, if the verb were zedotat with the present tense and the continuous aspect, it would express that the paper remains torn now.

Sentences with the future tense express events which will happen in the future. Note that the future tense does not imply intention unlike English “will”.

- cákis a ces ca fêd te loj i saq.

- He will come here at night tomorrow.

The indeterminate tense is used for facts which hold at any time.

- vahixos okôt a laxol.

- Human beings certainly die.

It can also express facts which hold for a relatively long period of time. For example, the fact that “he can speak Shaleian” will become false when he dies, but it is unchangeably true for the long period during which he is alive. Thus, it can be expressed with the indeterminate tense.

The indeterminate tense is also used to express just an action without specifying when it is done.

- sâfat a tel e kin likomos a tel e nayef.

- I like to look at flowers.

In this example, “looking at flowers” indicates an action neither in the present time nor in the past, but an action itself of looking at flowers. In such a case, the indeterminate tense is appropriate.

§33.Aspects

Shaleian has six aspects: inceptive, progressive, perfect, continuous, terminative and indeterminate. Among these, the inceptive, perfect and terminative aspects represent a certain moment in time, and are termed generically “momentaneous aspects”. The progressive and continuous aspects represent a certain period of time, and are called collectively “durative aspects”.

First, we look at the momentaneous aspects. The inceptive aspect indicates the moment at which an act begins.

- lîdaf a tel e xoq afik.

- I have just started to read this book.

This sentence says that the present is exactly the instant at which the act of “reading the book” begins.

The perfect aspect indicates the moment at which an act is completed.

- feketak a tel te sot.

- I have just got up now.

The terminative aspect indicates the moment at which the state after an act is finished ceases to hold.

Next, we look at the durative aspects. The progressive aspect represents the period from the start of an act until its completion, or in other words the interval between the inceptive and perfect aspects.

- terac a tel te sot e rix.

- I am drinking water now.

The continuous aspect represents the period from the completion of an act until the end of the state after the completion, that is to say, the interval between the perfect and terminative aspects.

- déqat a tel.

- I am sitting down.

The indeterminate aspect is rather peculiar. It represents a whole act between the inceptive and perfect aspects.

- sôdes a tel e ric te tazik.

- I ate fish yesterday.

It is also used to express an action itself represented by a verb without specifying its aspect. This use is similar to using the indeterminate tense when one does not want to specify the time as explained in Section 32.

- haros e tel a kin lanos a'l ca zîdsax.

- I feel pleasure in going to school.

The following is a summary of the use of the aspects taking the verb “sitting down” as an example. When “sitting down” is used with the inceptive aspect, it indicates the instant someone begins to bend his/her knees to sit down. The progressive aspect indicates the period from the beginning of bending his/her knees until his/her buttocks get on the seat, and the perfect aspect represents that moment of getting seated. Since the continuous aspect represents the period in which the state caused by the act continues, it expresses that his/her buttocks are on the seat at that time. The terminative aspect indicates the moment his/her buttocks get apart from the seat. The indeterminate aspect represents the interval between the moment of beginning to bend his/her knees and that of putting his/her buttocks on the seat, or it expresses the act “sitting down” itself without mentioning its aspect.

Some of other languages use an aspect to express iteration, but Shelaian does not treat it as an aspect. We will discuss in Section 37 how to express iteration.

§34.Transitivities

Actions are divided into two groups. One consists of those which one can carry out all by oneself, while the other consists of those of helping someone to do something. In Shaleian, verbs for the former and the latter are called “intransitive” and “transitive” respectively. For example, “lie down” is an intransitive verb and “lay down” is a transitive one.

Note that the notion of intransitive and transitive verbs in Shaleian is completely different from that which concerns the existence of an object. Also take account of the difference between transitive verbs and causative expressions: a transitive verb means “to help someone to achieve it”, while a causative expression means “to make someone do it without assisting”. Consider for example the distinction between “put someone to sleep” and “make someone sleep”.

Shelaian uses the same word for intransitive and transitive verbs, and distinguishes them by its conjugation. See Section 17 for how verbs are conjugated.

Objects of assistance of a transitive verb are indicated by a li-phrase.

- déxes a tel.

- I slept.

- déxez a tel li yaf.

- I helped my sister sleep.

Special verb structures

§35.Auxiliary uses of verbs

Some verbs that can take a kin-clausal phrase allow omitting the kin and accompanying preposition. This is called an “auxilirary use of a verb”.

We will explain the expression of possibility as a representative example of such a use. To express possibility, the verb kil, which means “be able to do …”, is used as follows:

- kilat a tel e kin ricamos a tel.

- I can swin.

Suppose that either there are no prepositional phrases, aside from the kin-clausal phrase, in the main clause, or there is at most one such prepositional phrase in the main clause that occurs in the same form in the kin-clause. Under these conditions, one can omit the prepositional phrase and kin in the main clause, as in the following sentence. The phrase in the kin-clause that is the same as the omitted one tends to be moved immediately after the verb.

- kilat ricamos a tel.

- I can swim.

In the case where the verb in the main clause has more than one prepositional phrases other than a kin-clausal phrase, such as in the sentence below, an auxilirary use is forbidden.

- kiles a tel te tazik e kin ricamos a tel.

- I came to be able to swim yesterday.

This expression is also used to form imperative sentences. Sheleian verbs do not have imperative forms, so the verb dit, meaning “order to do …”, is used together with the lexical verb. Here, dit appears as an intransitive verb with the present tense and the continuous aspect. One cannot omit the object of the command.

- ditat lanis a loc e zîdsax.

- Go to school.

Since this is rather verbose, ditat is often contracted to di'. In spoken language, ditat itself is sometimes omitted. We will see this phenomenon in Section 68.

Verbs which allow the auxilirary use are limited; that is, meeting the conditions does not automatically allow its use. Verbs which allow the auxiliary use include kil, qif, raf, doz and vom.

§36.Verbal infinitives as nouns

Verbal infinitives that are not conjugated at all can be used as nouns meaning “the act of doing …”, that is to say, as gerunds.

A nominal use of a verbal infinitive replaces a kin-clause by a nominal phrase without kin. We will take the following sentence as an example:

- salot e abûd a kin folesos a zis e kadeg ca zis.

- It is bad to throw a stone at someone.

This sentence uses the verbal form folsesos of the verbal infinitive foles in the kin-clause. By changing the verb into the nominal foles, as well as changing the prepositions in phrases qualifying it into their nonverb-modifying forms, one can make a sentence which has the same meaning as the previous one. At this time, prepositional phrases that contain obvious elements such as tel or zis may be omitted.

- salot e abûd a foles ie kadeg ica zis.

- It is bad to throw a stone at someone.

However, this nominal use is not so frequently used. There is a tendency to avoid it when there are many prepositional phrases qualifying the nominalised verbal infinitive.

§37.Expression of iteration

To express the repetion of an action, the verb vom, which means “to repeat”, is used. The verb vom often takes the auxiliary use, explained in Section 35. The beginning, continuance and completion of an iteration are expressed by conjugating vom in the inceptive, progressive and perfect aspect, repsectively.

- vomak lîdos a tel e xoq afik.

- I have finished reading this book.

Note that the completion of an iteration and the perfect aspect have different meanings. Since the example above expresses an iteration, it indicates that the last iteration of repeating the action “to read the book” has been completed. If it began with lîdak a tel with the perfect aspect, it would express that the one-time action “to read the book” has been finished. The former expression implies that “I” have read all the way through the book, while the latter implies that “I” have simply finished the one-time action without mentioning whether or not “I” have read through the book.

Habits are a kind of iteration, so they are also expressed with vom. Habits that are still being kept at the present are expressed with vom conjugated in the present tense and the progressive aspect. Habtis in the past are similarly expressed with vom in the past tense and the progressive aspect.

- vomac vilisos a tel te pôd atov.

- I run every day.

Passives

§38.Passive-like expressions

Shaleian does not distinguish between the active and passive voices. The difference between the active and passive voices is that the topic of a sentence with the active voice is the subject, while that of a sentence with the passive voice is the object. As mentioned in Section 23, one can specify the topic by exchanging the prepositional phrases. For that reason, different structures are not needed to distinguish the two voices.

- sâfat e ces a zis aves.

- He is loved by everyone.

In this example, the e-phrase, which indicates the object, expresses the topic, giving a similar meaning as the passive voice.

Such an expression is sometimes called a “passive-like expression” in comparison to other languages which have the passive voice, but note that it is not syntactically special in Shaleian.

Comparison

§39.Comparatives

To express which of two items being compared is greater by some standard, one uses the adverb emic, meaning “more”, and the conjunction ni, the Shaleian equivalent of “than”.

In order to form an expression for comparison, one first makes a sentence without the object of the comparison.

- salat a kadeg afik e adôg.

- This stone is heavy.

Then one makes a sentence mentioning the object of the comparison. This sentence must have the same structure as the first one.

- salat a doldaz e adôg.

- Elephants are heavy.

Finally, one puts the conjunction ni before the sentence about the object of the comparison and joins it to the first sentence. At the same time, mic, which means “more”, is placed after the adjective or adverb that expresses the standard of the comparison in the first sentence. The word mic is used as an adverb and put immediately after the word indicating the standard.

- salat a kadeg afik e adôg emic, ni salat a doldaz e adôg.

- This stone is heavier than elephants are.

Since the repeated expressions in this sentence are redundant, the common part is omitted from the ni-clause. Note that verbs cannot be omitted, so the proverb l is used instead. We will explain the proverb later in Section 54.

- salat a kadag afik e adôg emic, ni lat a doldaz.

- This stone is heavier than elephants are.

If it is sufficient to mention a single noun as the object of comparison as in the example above, then ni can be changed into its nonverb-modifying form, ini, with the noun as the object. Here, the ini-phrase is moved to lie immediately after emic.

- salat a kadag afik e adôg emic ini doldaz.

- This stone is heavier than an elephant.

The particle ile, the nonverb-modifying form of le, is used to show the degree by which something differs from the object of comparison.

- salat a tel e alot emic ile mulôt il'25 ini ces.

- I am 25 cm taller than him.

Comparative constructions are also used to express a factor by which one thing exceeds another, with an ile-phrase being used for the factor.

- kilat vilisos a tel ovit emic ile vâl il'aqot ini ces.

- I can run twice as fast as him.

ni- or ini-phrases can be omitted. In this case, the sentence shows a vague comparison, such as one comparing something to the average.

- salot a zecel afik e avituf emic.

- This problem is simpler.

This sentence means that the problem in question is simple compared to other existing problems.

Up to now, we have been looking at examples where the object of comparison can be in an ini-phrase, but there are natural examples where this is not the case. We show such an example below.

- salot a xoq aquk e anisxok.

- That book is interesting.

Below is another sentence related to the object of comparison.

- revat a loc e'n salot a xoq aquk e anisxok.

- You think that book is interesting.

When these two sentences are linked together in a comparative construction, we get the following.

- salot a xoq aquk e anisxok emic, ni revat a loc e'n salot a xoq aquk e anisxok.

- That book is more interesting than you think that book is interesting.

Eliding the shared parts gives us the final result.

- salot a xoq aquk e anisxok emic, ni revat a loc e'n lot.

- This book is more interesting than you think.

To express a comparative construction meaning “less”, one uses domic instead of mic.

- salot a loc e asokes edomic ini ces.

- You are less important than him.

§40.Equatives

Sentences expressing that two things are roughly equal by some measure can be formed in a similar way as comparatives. The adverb evêl is used to mean “about equal”.

We explain how to construct such a sentence. First, we form a sentence without the object of comparison.

- salot a qos e ahál.

- That person is cute.

Next, we create a sentence about the object of comparison with the same structure as the first one.

- salot a fakrêy i tel e ahál.

- My girlfriend is cute.

Finally, we attach the conjunction ni to the sentence with the object of comparison and link it to the first sentence. Then we attach vêl, meaning “about equal”, after the word that expresses the standard of comparison.

- salot a qos e ahál evêl, ni salot a fakrêy i tel e ahál.

- That person is as cute as my girlfiend is cute.

If we omit the redundant items in the ni-clause or replace it with an ini-phrase to avoid redundancy, then we get the following sentence.

- salot a qos e ahál evêl, ni salot a fakrêy i tel.

- That person is as cute as my girlfiend is.

- salot a qos e ahál evêl ini fakrêy i tel.

- That person is as cute as my girlfiend.

Instead of using an ini-phrase as described above, one can also join the items being compared with the conjunction o.

- salot a qos o fakrêy i tel e ahál evêl.

- That person and my girlfiend are about equally cute.

In the example using ini, only the subject qos is the topic, but in the example using o, both qos and fakrêy i tel are the topic. This is how the two expressions differ in nuance.

§41.Superlatives

The adverb ehiv, meaning “the most”, and the preposition ive, meaning “within”, are used to express that something is the greatest within a certain range.

As shown below, a superlative sentence is constructed by first creating an ordinary sentence without the group being compared to.

- kilat vilisos a fes ovit.

- This person can run quickly.

Next, the adjective or adverb hiv, meaning “the most”, is attached to the standard of comparison, and the range of comparison is expressed in an ive-phrase. The ive-phrase immediately follows ehiv.

- kilat vilisos a fes ovit ehiv ive refet i tel.

- Out of all my friends, this person can run the fastest.

The superlative construction is also used to express that something is at a certain rank within the range. The rank is expressed with an ile-phrase.

- pa salot a solkut apek e avâc ehiv ile cav axal?

- Which country is the fifth biggest?

Furthermore, the ive-phrase showing the range of comparison can be omitted as in the above example. When it is omitted, the range is assumed from context.

To show that something is the least instead of the greatest, one uses dohiv, meaning “the least”, instead of hiv. dohiv is used in exactly the same way as domic.

Relative constructions

§42.Relative constructions

Two sentences can be joined to form one in which one sentence modifies a noun in the other. This is called a “relative construction” in Shaleian.

We give an example of how to construct such a sentence. First, we start off with the prerequisite sentence below.

- salot a qos e qazek.

- That person is a man.

The following clause should modify qazek in the previous sentence.

- câses a tel e ces te tazik.

- I met him yesterday.

If we suppose that the word ces in the second sentence represents qazek in the first sentence, then we can join these two sentences to mean “that person is the man whom I met yesterday”. To do so, we first note that the second sentence is the one to modify a noun and omit the noun with the same meaning as the modified word. The lone preposition that arises is moved to be immediately after the verb. The modifying sentence is then placed immediately after the modified word. The clause modifying the noun is thus called a “relative clause”.

- salot a qos e qazek câses e a tel te tazik.

- That person is the man whom I met yesterday.

When the preposition accompanying the omitted noun modifies the head noun, as shown below, changing its position itself changes the meaning. In that case, the entire prepositional phrase of the modifying verb that contains the modified noun is moved immediately after the verb.

- sokat a tel e tiqat salot a qâz i e lasác.

- I know a boy whose father is a teacher.

If we had moved only i in the preceding example, we would have salot i a qâz and the reader would not understand what i was modifying. Therefore, we move a qâz i in its entirety to lie immediately after the verb.

If the noun modified by a relative clause is modified by other adjectives, then the relative clause is placed in the back, in the order noun + adjective + relative clause.

- qetat vo sokul i tel a zeqil avaf ebam séqes e ca tel a ces.

- Inside my room, there is a very large desk that I received from him.

In this example, zeqil is modified by two items: the adjective avaf ebam and the relative clause from séqes on.

The tense within a relative clause shows time relative to the tense of the main clause. For instance, if the main clause were in the past tense and the relative clause were in the present, then the relative clause would represent the present within the past and therefore describe an event that had occurred the past.

§43.Nonrestrictive relative clauses

Relative clauses fundamentally restrict the nouns that they modify. To put it another way, the noun “man” in qazek câses e a tel, which refers to a broad set of objects, is restricted, and its meaning is narrowed to “a man whom I met”. On the other hand, if we inserted a tadek before the verb starting the relative clause, then the relative clause would add supplementary information without narrowing the meaning of the noun. This is called a “nonrestrictive relative clause”.

- salat e aqobit a beqas aquk, salat a e qazrêy i refet i tel.

- That man, who is my friend's boyfriend, is unfriendly.

If additional prepositional phrases are added after a nonrestrictive relative clause, then a tadek is required a the end of the relative clause.

- salat a beqas aquk, salat a e qazrêy i refet i tel, e aqobit.

- That man, who is my friend's boyfriend, is unfriendly.

This use of a nonrestrictive relative clause appears when the modified noun is limited to one referent with words such as fik or cik or by being a proper noun.

Conjunctions

§44.Connectives

Shaleian has five connectives: o, ò, é, á and à, which connect two phrases or clauses in an equal relationship. For that reason, the meaning does not change, even if the phrases or clauses connected are switched in order. Out of these, ò, é, á and à have alternate forms lo, lé, lá and dà, which are used only to connect a clause to another clause.

When a connective connects two phrases, it can be inserted between the words to be connected.

- cikekat a tel e dev o miv.

- I have a pen and some paper.

Not only can nouns be connected, as above, but also other kinds of phrases such as adjectives and verbs.

- debat o dojat e tel.

- I'm tired and worn down.

When a connective connects two sentences, it is placed before the sentence, and a tadek is inserted between the two clauses. If the connective phrase is short, this tadek may be omitted at one's discretion.

- kavat a tel e xoq avôl, dà dulîdes a tel e met arak.

- I have a lot of books, but I haven't read any of them.

§45.Particles

Particles can be used both as prepositions and conjunctions, but see Section 20 and Section 21 for the use of particles as prepositions. In this section, we explain how particles are used as conjunctions.

The basic use of particles as conjunctions is to connect two clauses. That is, the conjunction is attached before one of the clauses, and a tadek is inserted between the two clauses. The clause with the particle used as the conjunction is called a “conjunction clause”.

- kavat a tel e xoq avôl, vade sêfat a tel e met.

- I have a lot of books because I like them.

Unlike with connectives, the entire conjunction clause can be moved before the main clause.

- vade sêfat a tel e xoq, kavat a tel e met avôl.

- Because I like books, I have a lot of them.

Furthermore, the tense of a conjunction clause, unlike that of a relative clause, is not decided relatively. In other words, a conjunction phrase in the past tense shows a past action, and one in the future tense shows a future action, regardless of the tense in the main clause.

When the entire conjunction clause is modified by some kind of word, that word immediately follows the conjunction.

- kômot a ces e levlis, te edif ricamos a ces.

- He wears glasses, even when he is swimming.

§46.Adverbial uses of conjunctions

Although the function of a conjunction is to join two clauses in a single sentence, there are situations when it merely has the meaning of connecting two separate sentences. This is called an “adverbial use of a conjunction”. In cases where one is used as such, a tadek is always placed immediately after the connective or particle used as a conjunction.

- kavat a tel e xoq avôl. vade, sêfat a tel e met.

- I have a lot of books. That's because I like them.

In the example above, the conjunction vade does not connect clauses because the sentence is cut off mid-way. However, it shows the relationship between the meanings of the former sentence and the latter one; namely that of effect and cause. If the tadek immediately following the conjunction used adverbially is removed, and the dek of the preceding sentence is changed into a tadek, the resulting sentence follows the ordinary use of a conjunction to join together two clauses.

§47.The conjunction kin

Shaleian has a special conjunction, kin. This conjunction means “the action of …” or “the state of …” and has the function of nominalising clauses. It takes the roles of the “to”-infinitive, the “that”-clause and the “wh”-interrogative clause of English. The nominalised clause is called a “kin-clause”, and the prepositional phrase to which the kin-clause is attached is called a “kin-clause phrase”.

- salot e asas a kin feraces a ces ca fax.

- It was good that he helped his mother.

In the example above, the clause under feraces has been nominalised and become the object of a.

If the entire content of a kin-clause is modified by some word, that modifier is placed immediately after the kin.

- haros e tel a kin etut yepelos a'l.

- The only thing that makes me happy is singing.

If etut were placed immediately after etut in the above sentence, it would not modify the entire kin-clause but rather only yepelos, and the sentence would mean “I feel good just by singing”.

kin can also be used to form indirect questions, as explained in Section 31.

Although kin is a conjunction, it does not have the role of connecting two items as other conjunctions do. The tense within a kin clause is relative to that of the main clause, as with restrictive clauses.

Numerals

§48.Numbers

Shaleian uses a base-10 system for counting. The numbers from 0 to 9 are read as in the table below.

| word | number |

|---|---|

| nof | 0 |

| tis | 1 |

| qec | 2 |

| yos | 3 |

| piv | 4 |

| xal | 5 |

| ric | 6 |

| sez | 7 |

| kaq | 8 |

| von | 9 |

Numbers with no more than four digits can be read by attaching the aforementioned numerals for each digit with the unit words shown below. If there are digits with value 0, then they are not read.

| word | number |

|---|---|

| et | 10 |

| il | 100 |

| as | 1000 |

For instance, 3487 is yosaspivilkaqetsez.

To read a number with five or more digits, one splits the digits into four-digit groups from the least significant end and reads each group of digits using the case above, with the unit words below between the groups. When such numerals are spelt out, fêks are placed immediately after the words listed below.

| word | number |

|---|---|

| otik | ten thousand (104) |

| oqek | one hundred million (108) |

| oyok | one trillion (1012) |

| opik | ten quadrillion (1016) |

| oxak | one hundred quintillion (1020) |

For instance, 517002 is saletisotik-seqasqot.

The numeral system described above is similar to that of Japanese. However, in Japanese, 51000 and 120 are read not as “五万一千” or “一百二十” but rather as “五万千” or “百二十”; the “1” digits are elided in Japanese, but tis cannot be omitted in Shaleian. For instance, 10 is tiset, and 11101 is tisotik-tisastisiltis.

When writing large numerals with digits, they are written with a space between groups of four digits, as in 51 7002, in order to make it easy to discern the size of the number.

§49.Use of numerals

At the core, numerals are used as adjectives. Therefore, they appear with the inflectional prefix a. Furthermore, this conjugated form still shows only the numeral itself.

Cardinal numerals are expressed by prefixing il' to the numeral conjugated as an adjective. Although this is a contraction of avôl ile lêk, the uncontracted form is not used except with a special meaning such as emphasis. The same form is used, whether the numeral is used as an adjective or as an adverb, and it follows the noun.

- kavat a tel e refet il'atisil.

- I have 100 friends.

Ordinal numerals are expressed by prefixing ic' to the numeral. Although this is a contraction of acál ile cav, the uncontracted form is rarely used as is the case with cardinal numerals. They are used in the same way as cardinal numerals, following the noun.

- ditat kòdas a loc e kofet i fax o qâz ca miv ic'afex.

- Write your mother's and father's names on the third sheet of paper.

§50.Nominal forms of numerals

As described in Section 49, the numeral used in cardinal and ordinal numerals are adjectives. Numerals used as such follow the reading rules described in Section 48 and may be spelt out or read.

On the other hand, when one wants to use a numeral as a noun, such as when showing the idea of “3” itself, the reading of the number changes. To be specific, the vowel of the final syllable is mutated according to the rules a → e → i → a and o → u → o. For example, 67 as an adjective is ricetsez, but as a noun, it is ricetsiz.

- salot a ricetsiz e atûl emic ini tisal.

- 67 is smaller than 100.

§51.Dates and times

To express dates, one uses ordinal numerals and connects the unit + ac' + numeral into a group. The units are lined up from the smallest first. For instance, “April 17” would be expressed as taq ac'17 ben ac'4.

To express times, tat ile is followed by the unit and the numeral. Unlike with dates, the units are lined up from the largest first. For instance, the time “8:12” would be expressed as tat ile tef 8 meris 12.

Although nouns are placed in succession in all sorts of expressions, these expressions of dates and times are recognised as a special case.

Omission and contraction

§52.Omission of prepositional phrases

Prepositional phrases, unlike verbs, are not always required in Shaleian. Consequently, they can be omitted freely according to grammar. However, the a-phrase, which shows the subject; the e-phrase, which shows the object; and the li-phrase, which shows the object when a verb is used as a transitive verb, are not omitted very aggressively.

A prepositional phrase that is not explicitly specified is interpreted to govern a pronoun of indefinite meaning, as explained in Section 65.

- bozetes e tel.

- I was hit.

In this example, the a-phrase showing the subject is omitted, and the one who performed the hitting is not explicit. In this case, the reader understands that the writer was hit by some particular person but is not referencing the attacker. To put it in other words, it is thought to be omitting a zis or a zat.

§53.Omission of repeated elements

Repeating words or phrases is considered verbose and disliked in Shaleian. For that reason, the repeated part is omitted from its second appearance forward. Because verbs are generally not allowed to be omitted in Shaleian, they are replaced with the proverb l when they should be omitted. In addition, when the same word appears several times, it is replaced with a pronoun of the same kind from its second appearance onward, as described in Section 65, avoiding its repetition. Furthermore, negative adverbs are not omitted, even when they are repeated. See Section 54 for information on the proverb l.

- nises a hîx zi abig ca azaf, ce nises a hîx zi azaf ca ajôm.

- The sky changed from blue to red, and the sky changed from red to black.

In this example, the verb nises and the prepositional phrase a hîx exist in both the former and latter clauses. For that reason, they are omitted as shown below.

- nises a hîx zi abig ca azav, ce les zi azaf ca ajôm.

- The sky changed from blue to red, and then from red to black.

First, a hîx is removed from the latter clause, and nises is changed to les by using the proverb.

In comparative and equative expressions, explained in Sections 39 and 40, the object of comparison is shown using the conjunction ini. As an exception, the verb in such an ini-clause may be omitted.

§54.The proverb l

When a verb is repeated, its second occurrence onward is replaced by l, known as the “proverb”, avoiding the repetition. This l stands in for the verb in the clause immediately preceding it and all prepositional phrases that modify it.

- kavat a tel e monaf. lat a ʻmelfih avoc.

- I have a cat. Melfia does too.

In the above example, lat stands for kavat e monaf.

§55.Contractions

The first-person pronoun tel, the second-person pronoun loc, as well as ces and cit, which refer to a person or object mentioned earlier, occur frequently in sentences. In order to reduce verbosity, they are often contracted as 'l, 'c, 's and 't, respectively, starting from their second occurrence in the same clause. In this case, there is no space between the preposition being attached to and the contracted form. In addition, these contractions can be used only from the second occurrence onward within a sentence; they cannot be used at their first occurrence. Moreover, they are rarely used except immediately after the six prepositions a, e, li, ca, zi and i.

- sâfat a tel e kin catos a'l vo fecil ica sod.

- I like walking in the surroundings of my house.

Furthermore, kin-clauses are used often; thus, kin is often contracted to 'n. This contraction can be used even for the first occurrence of kin in a sentence.

- cipases a tel ca ces e'n fegis a's e dev.

- I asked him to buy a pen.

§56.Abbereviations for dates and times

Expressions for dates and times can be abbreviated by writing the numerals separated by kaltaks. In this case, the year takes four digits and other numerals take two digits; if a numeral does not have enough digits, then it is padded with the digit 0 on the left. As explained in Section 51, dates are written with the smallest unit first in Shaleian. Note that this order is opposite of the Japanese order.

- zêfes a tel vo fêd te 12:05.

- I arrived at 12:05.

The expression 12:05 in the above example is short for “five minutes after twelve o'clock”, or in other words, tat ile tef 12 meris 5, but it could also stand for “May 12”, or taq ac'12 ben ac'5. They cannot be distinguished from the abbreviation alone, only from the context.

When reading this abbreviation aloud, the numerals delimited by the kaltaks are pronounced in succession. For instance, 12:05 would be read as tisetqic-xel.

§57.Creating compounds

When one wants to show a noun modified by an adjective clause or such, there are times when repeating it would become too verbose, and using ces or cit in its place would raise ambiguity about what the pronouns are referring to. In this case, the noun in question and the words considered the most important among the modifying elements are connected into one word with fêks, and the resulting word can be used as a pronoun. For example, if an earlier sentence contained the noun phrase zas kilat lakos a qi qixaléh, then that person could be referred to again by using zas-qixaléh, connecting zas with a word from one of the modifying elements, qixaléh.

Rhetorical expressions

§58.Insertion

As explained in Section 20, an adverb modifying a verb falls immediately after the verb or at the end of a sentence; however, they can also be placed between two prepositional phrases, provided that tadeks are placed before and after the adverbial phrase. This is called an “insertion of an adverb”.

- lanes a tel, otet, ca cêd.

- I go there, sometimes.

When an adverb is used in the middle of a sentence as such, it has a nuance of clarifying the verb in a complementary way. In the above example, the main information is “I go there”, but the information of “sometimes” is felt to be added against that.

§59.Emphasis

By moving a verb-modifying prepositional phrase placed after an ordinary verb before the verb and placing a tadek after it, that prepositional phrase can be emphasized.

- e ʻmelfih, cafeles a tel.

- Melfia is the one I called.

An adverb modifying a verb can also be emphasized in the same way.

- okôk, ditat lesis a'c e cal.

- Make sure to do that.

A verb-modifying prepositional phrase or adverb can also be emphasized by placing it at the end of a sentence and placing a tadek before it. Compared to moving it before the verb as described earlier, this method gives less emphasis and is used for reminders of new information at the end of a sentence and such.

- raflesec a tel te cal, e ʻmelfih.

- The person I talked to back then was Melfia.

Adverbs and adjectives that modify something other than a verb cannot be emphasized in this way.

§60.Admiration

An expression of admiration is formed by using s'e followed by an adjective or noun.

- s'e ayerif.

- How beautiful.

- s'e neyef ayerif.

- What a beautiful flower.

The s'e used in this construction is a contraction of salat e and can be used only in admirative expressions.

§61.Irony

When the padek at the end of an interrogative sentence (explained in Sections 28–30) is replaced with a dek, it becomes an expression of irony that shows that the content of the question is false. When read aloud, the sentence lacks any rising intonation at its end.

- pa kilat lesos a pas e cal.

- Who could do that.

Other special expressions

§62.Nonrestrictive uses of adjectives

Although adjectives have the function of restricting the nouns that they modify, an adjective can be made to not restrict its heads by placing tadeks before and after it. If the adjective occurs at the end of a sentence, it simply receives a tadek before it. In this case, the adjective is understood to supplement the meaning of a noun. This construction is called a “nonrestrictive use of an adjective”. The change in meaning is the same as that of nonrestrictive relative clauses, explained in Section 43.

- kavat a ces e yaf, ahál.

- I have a younger sister, who is cute.

§63.Alternative expressions for relative clauses

Some relative clauses can be expressed more concisely by using nonverb-modifying forms of particles.

Consider the following sentence as an example.

- salet e alot a qazek qetat a vo vosis afik.

- The man who was in this store was tall.

By omitting the verb in this relative clause and changing the prepositions of the prepositional phrases modifying the verb to be in their nonverb-modifying forms, we can express the sentence without using relative clauses.

- salet e alot a qazek ivo vosis afik.

- The man in this store is tall.

This expression can be used as long as the sentence remains unambiguous when the verb is omitted. In most such cases, the omitted element is recognised as qet, and the prepositions used in such cases are often ivo, ite, ifi or ide.

§64.Clarification of pauses

When a prepositional phrase with a noun phrase modified by a long relative clause occurs in the middle of a sentence, it can become hard to discern where the prepositional phrase ends.

- câses a tel e tiqat lanes a e zîdsax te tazît.

- I met a boy who was going to school yesterday.

In the example above, it is unclear whether the relative clause under lanes, modifying tiqat, ends at e zîdsax or at te tazît. If the relative clause ends at e zîdsax, then a tadek can be inserted after the delimited part in order to make this divide clear.

- câses a tel e tiqat lanes a e zîdsax, te tazît.

- Yesterday, I met a boy who was going to school.

In addition, this use of the tadek tends to be kept at a minimum. If the prepositional phrase were moved immediately after te tazît or a tel in the above sentence, then no explicit demarcation would be necessary. However, if te tazît were new information to be presented to the reader, then it is preferred to be at the end of the sentence as explained in Section 23, and a tadek is likely to be used for clarification.

Other important words

§65.Proforms

The words in the table below are collectively called “proforms” in Shaleian. As shown in the table, there are ten kinds of meanings and five kinds of targets indicated by these words, with a total of 41 proforms. Note that the term “proform” is a generic term for the words in the table, and it represents neither sort nor category.

| f- | q- | c- | p- | d- | z- | k- | r- | m- | v- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | fes | qos | ces | pas | dus | zis | kos | ris | ves | |

| object | fit | qut | cit | pet | dat | zat | kut | rat | met | |

| event | fal | qel | cal | pil | dol | zel | kel | rel | ||

| place | fêd | qôd | cêd | pâd | dûd | zîd | kôd | rîd | ||

| qualifying | fik | quk | cik | pek | dak | zak | kuk | rak |

Since proforms with a common meaning share the first letter, such groups are sometimes named after that letter. For example, the group with fes, fit, fal, fêd and fik are sometimes called “f-proforms”. They can also be named after what they indicate, as listed in the following. The proforms in aforementioned group are called the “proximal proforms”.

| kind | name |

|---|---|

| f- | proximal |

| q- | distal |

| c- | demonstrative |

| p- | interrogative |

| d- | negative |

| z- | indefinite |

| k- | assertive |

| r- | elective |

| m- | substitutive |

| v- | generic |

Proforms indicating persons, objects, events or places can be used only as nouns, while qualifying ones can be used only as adjectives.

Proximal and distal proforms show whether something is near or far from the writer. This distance can refer to physical distance, but also to psychological distance. There is no distinction between genders as in English “he” or “she”.

- salot a qos e qâz i tel.

- That person is my father.

The demonstrative proforms refer to something mentioned in an earlier context. It corresponds to Japanese “それ” or “そこ”.

- vade salot a qinat afik e asokes o axodol ebam, ditat yalfesis a loc e cit.

- Because this painting is very important and expensive, please take good care of it.

Interrogative proforms are described in Section 29, and negative proforms in Section 25.

The indefinite proforms refer to something in general without specifying a particular instance thereof. For instance, zas refers to people in general without pointing to anyone specifically. They are almost always modified by another word and vaguely indicate “people”, “things” and so on.

- pa salat e pas a zas xarat e a ces?

- Who is it whom he loves?

The assertive proforms are used when there is a particular instance of something but what it is specifically is not referenced. In this case, the person using one does not need to know what is being referred to specifically, and the only requirement is that there is exactly one referent. In other words, its meaning is equivalent to “some” in English.

- vade cipases a kos ca loc, ditat delizis a loc zi ces.

- Since someone has asked you, please follow their order.

The elective proforms has the meaning of “any”. They are often used to express compromise.

- bari kodis e rel, xarit a tel e loc.

- Even if anything happens, I'll still love you.

There is only one substitutive proform, met, which takes a noun mentioned earlier in context. However, met does not refer to the same thing as the earlier noun, but rather a different instance of the same noun. It is roughly equivalent to “one” or “ones” in English.

- kûtat a nîl i tel e sokul iku ces, dà dulat a tel e met.

- My older brother has his own room, but I don't.

There is only one generic pronoun, ves, which refers to a person. It is used to describe a common opinion. Its usage is similar to that of “on” in French.

- qîlos a ves e dev so kòdos a ces e lakad.

- One uses a pen to write characters.